By David-Elijah Nahmod

Poet Flower Conroy has been creative since her childhood. While growing up in New Jersey, she was always making arts and crafts, such as Christmas ornaments and jewelry. She would also draw, making up stories to go along with her pictures, which she stapled into little books. Eventually, she realized that her stories were more like poems, and so she began writing poetry. She is now a published and respected poet, with five well-received books available for purchase at Amazon. Conroy’s work has also brought her acclaim. A former resident of Key West, Florida, she was once the Key West Poet Laureate. She is also a National Endowment for the Arts Fellow.

“What drew me to poetry is its infinite ability to gather, to juxtapose,” Conroy, who lives with her wife, said in an interview. “Though I didn’t quite have that language/overt sense of aesthetic when I was younger. It was an escape to where there were dragons and enchanted fields. I could be someone else on the page, someone far more interesting than I was.”

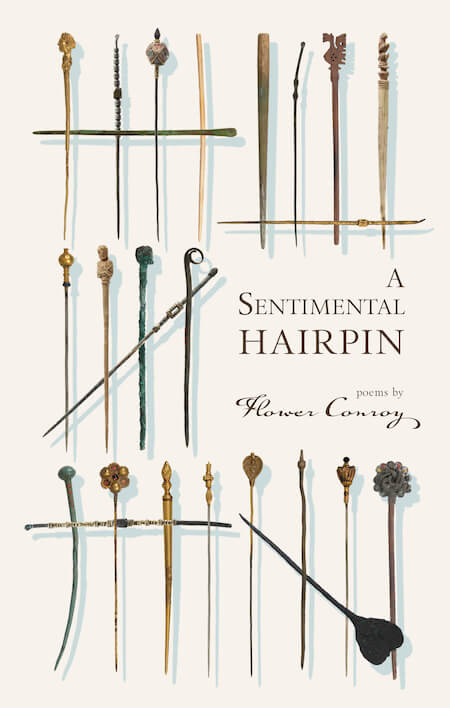

Conroy’s latest collection, A Sentimental Hairpin, was recently published by Tolsun Books. In this work Conroy writes about a very personal part of her life with candor: her mother’s stroke and her experiences as a caregiver during the time that her mother was physically disabled. This wasn’t her first time dealing with a gravely ill parent. In her early 20s, Conroy lost her father, who was only 45 when he passed. As she tells it, her father’s heart had stopped. Paramedics arrived and revived him, lost him a second time and revived him again. But the second revival was in-body only. Her father lay in a coma for a year until the family pulled the plug.

“I’ve not wholly recovered from that, losing him so young and in such a graphic way,” Conroy said. “So when my mother went into the hospital for a stroke, I was flipping out. I’m hesitant to say re-triggered, but my mind went there. I wasn’t quite sure what was going on. This was during Covid and my mother lives in New Jersey and I was living in Key West.”

Conroy calls the poems that deal with her mother’s illness the “Love in the Form of” poems, because their titles all begin with those words, such as Love in the Form of Bleach, in which she recalls her mother’s visit with a doctor. The poem reads, in part:

“On the video chat the doctor instructs she lift

her arms. Then: Hold them out, like carrying

a pizza box. Now close your eyes.

When she shuts her eyes she lets fall

her arms. Because she’s hard

of hearing, the nurse & I encourage her

to again hold the make-believe box,

Now close your eyes. She cups her hands

to her face as if covering her nose

& cheeks with invisible cheese.

When we finally get her to extend

her arms while shutting her eyes: See

how the right arm hovers lower? She wants

to come home; take a shower; sit in a chair.

I need another day or two.

My laboring’s only just beginning.”

Conroy spoke of how it affected her emotionally to write about the experiences with her mother.

“Writing is what I do, so I would have been more lost not writing,” she said. “I wasn’t overthinking when I was writing them, I was swept up in the moment, I was overwhelming the page with what was going on inside of me.”

Some of the poems, Conroy recalls, were quite angry, such as one where she touched upon the time when her mother’s best friend came to visit after her mother was released from the hospital. The friend brought her mother a pack of cigarettes.

“But that wasn’t ultimately a poem, it was me venting,” Conroy said. “And I allowed myself to write those poems. The uglier moments, the frustrations and griefs and grievances. And what was distilled into poetry stayed and what was emotional vomit went. Reading the poems now there’s a small sense of relief that that has passed, that my mother is healing.”

Conroy points out that there’s a difference between caregiving for someone during an extended stay and caregiving full time. Both her mother-in-law and sister-in-law are disabled, and both have lived with Conroy and her wife for more than a decade. In her mother’s case, there were additional challenges as her mother lives with diminished hearing.

“When I was there, she wouldn’t hear the tea pot screaming in the kitchen, so I’d shut it off,” Conroy recalls. “She had difficulty hearing the doctors. So of course I worried if I wasn’t there, what might happen.”

In addition to the stroke, her mother was diagnosed with diabetes. Now, on top of all the pills she had to take, Conroy’s mother had to prick her finger and measure her blood sugar. But because she was still recovering from the stroke, she sometimes had to prick herself repeatedly until she could get a reading.

“After the open-heart surgery, she couldn’t sleep in her bed,” Conroy said. “She couldn’t bathe herself or get the medical sports bra on without help. Even combing her own hair was difficult.”

All kinds of challenges would present themselves while Conroy was caregiving for her mother. When she was at her mother’s house, she found herself deep cleaning simply because it needed to be done. She found it cathartic to make the house as pleasant and as safe as possible. To that end, Conroy had her uncle install grab bars by the toilet at her mother’s house and did some rearranging so that her mother could get around with her walker.

“I wish I could say I kept myself grounded and emotionally healthy during this experience,” Conroy says. “I mean I did, but not without also self-medicating and the poems address this.”

And yet she found ways to help keep herself in as good a place as possible during this experience. She would call home and talk to her wife, she would concentrate on helping her mother, which she found also helped her. She would write, and writing, she says, saved her.

“I’d go for walks around her yard,” she adds. “I’d gather fallen branches and found myself building what I call a fairy hut in the corner of the yard where I’d leave seeds for the birds and squirrels. My cousin, who’s more like my brother, and his husband would spend the weekend at my mother’s and we’d play Scopa or Shut the Box. Spending time with them was a balm to the soul.”

Conroy’s advice to anyone who might be caregiving for someone with a disability is simple: develop a “do unto others” approach.

“If I had to rely on someone else helping me bathe or dress, how would I want to be treated?” she asks. “To go slow and have patience. To listen and anticipate. Ask for help when you need it.”

A Sentimental Hairpin, as well as Conroy’s earlier books of poetry, are now available through online bookstores.