By John Whittier Treat

In my home growing up, Thanksgiving was little different for me than any other dinner — the bounty of food and rarely seen relatives notwithstanding. I was as silent as always. I did not speak unless spoken to, and my family had long ago learned not to put this stammering child on the spot by asking him any but the most necessary questions — those answerable by a positive nod or negative shake of the head. More turkey, John? A nod yes. But the follow-up question that everyone else at the table got — White or dark? — was omitted. I got either, or both, whatever my wishes might have been.

A stutterer at meal times can avoid having to talk by keeping his or her mouth full. This tactic is surprisingly successful, but cannot be deployed before the meal actually begins, and in my family, Thanksgiving was the one time each year that saying grace preceded eating. We don’t read it, write it, or think it. We say it. You cannot nod or shake your head through the litany. Someone must enunciate the words, say each clearly enough for all to hear. Fortunately, this task fell onto the patriarch of the clan and not his stuttering eldest son — me. Thank you, God, for the food we are about to eat.

In my boyhood, th- and f-, two voiceless, labiodental, fricative consonants, would have been unsurmountable. Rather than risk embarrassment, I was spared them, even after my father was gone and I, the eldest son, was then the patriarch. My mother assumed that duty until her own passing, and now there are no more Treat family Thanksgivings.

We give thanks at this time of year, in the tradition of the Pilgrims, and it is good that we do. We should give them more often. Whether we say the thanks or only listen to them, they merit our close attention. Thank you. But here is the thing about thankfulness: besides being a word with two problematic consonants in it, it is something you experience alone, even sitting at a table crowded with those people closest to you. It is an emotion, a feeling, and it stops there, within you, and goes nowhere else. But it is also transitive: you are thankful for something — your entire life, or maybe just that plate of food before you. Being thankful means you are obliged or indebted to something outside yourself that, should it disappear, means you need no longer be thankful, only bereft.

This is why we say grace and not just express thanks. “Grace” is a Middle English word with a root in Latin gratus, also the origin of its close cousin “gratitude.” But thankfulness and gratitude have parted paths in how we use them today. In both my traditions — the Quakerism I embraced after a Catholic childhood, and in what lessons I’ve learned in an adulthood spent in and out of recovery for substance abuse — gratitude is something more than a subjective state of being, however necessary it may be to experience it as that, too. Gratitude is a thing, and you must be practical with it and pass it on to others. It is social. Gratitude is not about your obligations or debts. It is not formal; in fact, you often improvise gratitude. It is a call to action. Gratitude may make its first moves within you, but it only becomes real when you gift it to others needing to recognize it in their own lives.

In AA and other twelve-step programs, gratitude forms one side of the coin that is your sobriety. (Serenity is the other.) Our literature puts it this way: gratitude “disposes us morally to act right and emotionally to feel right, to do good as regards others and to do well as regards our own mental condition.” Gratitude is something we practice. What does it mean to be, as we often hear at meetings, “a grateful alcoholic?” It means we have something to share with others. Gratitude is why there is a twelfth step in all twelve-step programs: your thankfulness is ready to graduate into a mission to practice gratitude “in all our affairs,” and those affairs will always involve other people.

Nowadays, some stutterers insist we should be grateful for our handicap. That it teaches us important — sometimes cruel — lessons about the fluent world around us we might not otherwise take to heart. I concede that point. When one of us, Lissa Lange (author of Chicken Soup for the Soul), writes “Without my stutter, and all the emotions and experiences accompanying it, I wouldn’t be as compassionate, patient, and understanding of other people with challenges,” I also understand how empathy ameliorates the world. But that is not where I choose to practice gratitude, because though gratitude might start with me, it does not end there. Rather than feel anger when someone finishes my stammered, incomplete sentence, for example, I will feel gratitude that someone has offered me help, however misguided. I will not feel gratitude that my disability limits me less than other disabilities might, because I am not so arrogant as to assume what any other person with a different disability is capable of. I will be grateful for this one day and of what I accomplished in it — an aware and sharable appreciation made possible.

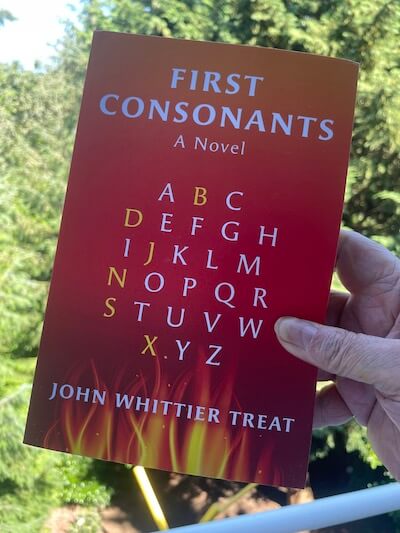

In my novel First Consonants, my stuttering protagonist Brian is consumed with grudges against the speaking world that make him act out in violence. But late in life, when he sees a sandpiper inexplicably surrender its life to a dog on a remote beach, he realizes his disability could always have been his own sacrifice, and not the cause of anyone else’s. Skeptical of the existence of God, he suddenly finds himself in a state of grace. And for that, he is grateful — if not exactly thankful — because what lies ahead of him will demand just the sacrifice he has postponed.

John Whittier Treat was born and raised in New England, but has lived in the Pacific Northwest for four decades, as well as for years in Asia. He now resides in Seattle with his husband, the mathematician Douglas Lind. An emeritus professor at Yale, he publishes fiction, essays and poetry in addition to continuing his academic pursuits. The Rise and Fall of the Yellow House (Big Table Publishing Company, 2015) a novel of the early years of the AIDS pandemic in the Northwest, was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Prize. He is the recipient of both the John Whitney Hall Prize in Japanese Studies and the Christopher Hewitt Prize in fiction, as well as a Pushcart Prize nomination. He is a 2020 alumnus of Antioch University’s MFA Program in Creative Writing and was a 2021 June Dodge Fellow at the Mineral School. A stutterer himself, Treat’s new novel, First Consonants, is the story of a family of stutterers set in the Alaskan outback and will be published by Jaded Ibis Press in 2022. He is excited about his work-in-progress, The Sixth City of Refuge, the story about two young gay men, one HIV+ and the other a meth addict struggling to quit, who leave Los Angeles for rural Washington State and find their lives caught up with the local survivalist subculture. Learn more at www.johnwhittiertreat.com.